Introduction

The DeFi space moves faster than you can blink, with different projects coming out daily. No matter what each and every project offers, they all share a key dilemma: incentivizing users to provide liquidity for their tokens. Providing liquidity is essential for growth and success, but as it has been proven in many cases, it is very hard to incentivize all parties and keep them happy.

Now enter the idea of ve(3,3). Ve(3,3) is a unique, economic development that focuses on balancing long-term incentives between LPers (Liquidity Providers), token holders, ecosystem projects, and DEXs. Andre Cronje, who created a plethora of DeFi projects, initially presented this idea, which combines the vote escrow tokenomics (‘ve’) from Curve Finance, with the (3,3) game theory design used by OlympusDAO.

There are a couple of issues with traditional DEXs since they incentivize liquidity instead of fees, which Cronje wanted to fix:

- The rewards from liquidity pools (LPs) are in the form of the DEX’s native token, which could face dilution as more rewards are distributed.

- There is no loyalty to the protocol. To keep LPers onboard, the protocol must offer a high APR, otherwise, the LPers would just migrate to another platform.

- If LPers are incentivized based on the amount of liquidity they provide, there can be too much liquidity for a low amount of fees, which is harmful to the protocol in the long run.

- Since LPs want the highest APY, most of the liquidity is in a couple of large pools, while the rest suffer from low liquidity. This can cause difficulties in buying or selling tokens with high slippage.

In order to best understand how ve(3,3) solves these issues, let’s break it down section by section starting with the (3,3) game theory framework.

(3,3)

OlympusDAO, the first implementer of (3,3), uses protocol-owned liquidity to give users extra yield on their LP tokens. How it works is they buy their liquidity from users (in the form of LP tokens or another specified token) in exchange for their native token ($OHM) at an average discount of 6–7%, in a process called bonding. These tokens are locked (staked) for a set amount of time (1-week minimum), with the longer it’s locked, the more yield it generates. This is a win for the buyer, as they get a discounted token. This is also a win for the protocol, because it adds money to the treasury (DAI, WETH, etc.) or owns an LP token, meaning owning liquidity you provided to a pool.

For example, let’s say Bob provided $100 to a LUSD/OHM pool on SushiSwap, and he receives an LP token worth $100. This LP token will be used if he wants to get his $LUSD and $OHM back from SushiSwap, but he decides to sell it to OlympusDAO for $107 worth of bonded $OHM. Then, OlympusDAO owns his $100 LUSD/OHM LP token, essentially owning the liquidity.

Using bonding, OlympusDAO can grow its treasury by collecting LP token fees, which raises the value of the treasury, and $OHM’s price. When $OHM’s price outpaces the market value in the treasury, OlympusDAO issues more $OHM to create more supply and decrease the price. When $OHM is underperforming compared to the treasury, OlympusDAO burns $OHM from the supply to increase its price. This keeps the $OHM value and the treasury synced.

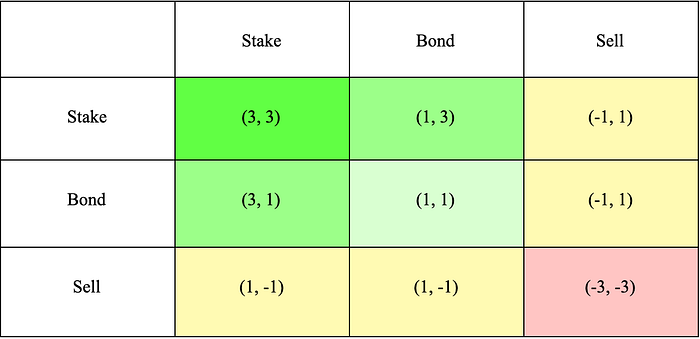

Both bonding and staking operations benefit the platform while selling the token negatively impacts the platform. Here is a table that illustrates the possible outcomes for users:

- If both users stake, it is the best outcome for them and the protocol (3+3=6)

- If one stakes and one bonds, it is also great because staking takes $OHM off the market and puts it in the protocol, while bonding provides more liquidity to the treasury (3+1=4)

- If both bond, it is still good for the protocol because it receives liquidity in the treasury, but also requires the protocol to give discounted $OHM tokens (1+1=2)

- If one user sells, it diminishes the efforts of another who stakes or bonds (1–1=0)

- When both users sell, it creates the worst outcome for them and the protocol (-3–3=-6)

With this model, the platform has a net positive, with users incentivized to either stake or bond. The platform then enjoys a net positive, and it’s a win-win.

Ve

The ve aspect of ve(3,3) comes from Curve Finance and stands for vote-escrowed. I will try not to go into too much detail covering every single aspect of Curve as there are a lot of resources out there for that. So for this article, I will only cover what you need to know to understand the ve(3,3) DEX structure.

So at its core, Curve Finance is an Automated Market Maker (AMM) which is a fancy term for a type of decentralized exchange. In a traditional order book structure, people trade by matching an individual buyer and seller. With an AMM, people provide liquidity into a pool in exchange for a share of the trading fees. Curve achieved its initial goal of creating an exchange specializing in low slippage and fees for stablecoins. Since 2020, it has grown and stands today as the largest DEX by TVL.

So in traditional DEXs like Uniswap, it is a simple system in regard to fees. People provide liquidity for a trading pair and then get trading fees proportional to their percentage of total liquidity, i.e. Bob provides $10 into a pool with $100 of total liquidity. If the pool generates $1 of fees, he will receive $0.10.

Curve is a bit more complicated. So $CRV (the native token of Curve Finance) was created to incentivize liquidity. At the end of the day, you need to have a lot of liquidity to provide low slippage. So to do this, the $CRV emissions (newly created $CRV) are given straight to liquidity providers. Now what is the utility of $CRV? The $CRV token has three main uses. But to receive these benefits, you need to first lock your $CRV. You can lock $CRV for a minimum time of 1 week all the way up to 4 years. If you lock your $CRV for 4 years, you will receive an equal amount of $veCRV since it is 1:1. But for any lock time less than 4 years, you will receive less $veCRV than that amount of $CRV deposited. This concept incentivizes people to lock for longer periods of time. As you can see there is a trade-off here. With a short lock time, you are losing a substantial amount of your position. But locking $CRV for 4 years also has its obvious risks since you can only receive your liquid $CRV once those 4 years have passed.

So now let's talk about the benefits you earn as a result of taking on this risk. There are three of them you get as a $veCRV holder:

- Staking: Earn 50% of all platform trading fees

- Boosting: Up to a 2.5x reward boost on your provided liquidity

- Voting: Vote on governance proposals and pool parameters

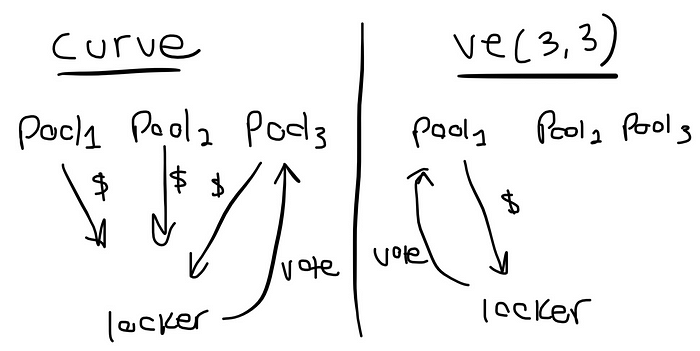

All the benefits are pretty self-explanatory except the last one in regard to pool parameters. Remember that people who provide liquidity get rewarded in newly minted $CRV. How these emissions are distributed to the different liquidity pools is determined by people who vote with their $veCRV. The percentage of votes that a pool receives is equal to the percentage of total emissions a specific pool gets.

As you can see from this structure, all parties are incentivized much better than before in Uniswap. Liquidity providers are incentivized to provide liquidity on the pair with the most votes so that they get more emissions. In return there is lower slippage/fees, more people trade on that pair, more fees go to the LPers and $veCRV holders, etc. Everyone’s happy, right?

Yes, but there are still some inefficiencies with Curve’s system: Lots of liquidity exists on trading pairs that don’t have a lot of trading volume. Also, people can vote for trading pairs that don’t generate fees, yet don’t get punished for voting inefficiently. Therefore, the main overarching question we are trying to answer is how do we best incentivize fees instead of liquidity?

ve(3,3)

Ok now that we know how Curve Finance and Olympus DAO work we can build off of that to understand how ve(3,3) DEXs function. Many aspects are taken from each protocol and expanded upon, hence the name ve(3,3). For example, the “ve” structure from Curve is taken directly. Users can lock the native token to earn protocol fees, vote in governance, and boost their own earnings on liquidity. So let us go through what makes it different and we’ll explain the impact of each.

Lockers earn all protocol fees

This is the biggest change and there is a lot to explain here so let’s dive in. Instead of earning 50% of the fees in Curve, lockers earn 100% of the fees. The fees are also distributed differently. So in Curve Finance lockers vote for a specific pool to delegate how emissions are distributed. This structure stays the same. But now, lockers only earn fees from the pool they vote on instead of a total share of protocol fees. To simplify the process further, the fees are paid out directly in the tokens that are being swapped (lockers who vote for an ETH/USDC pair will earn rewards in $ETH and $USDC)

There are a lot of positive impacts from this change. People are now incentivized to vote for the pool with the highest trading fees (which generally correlates with the pair that has the most trading volume) since they will maximize rewards that way and not voting correctly will result in not receiving as many rewards. Also, with more people voting for that pool, there will inherently be more liquidity since liquidity providers will want to earn the most emissions. Now you can see how the incentives are aligned for LPers and lockers.

Outside protocols can place bribes on trading pairs

One main problem in DeFi is that it is tough for new protocols to bootstrap, or gain a lot of liquidity for their token in its early stages. “Bribing” helps to solve this issue. These newer protocols can put “bribes” or extra rewards that are received from people who vote on their token pair. Therefore, people who vote for a token pair with a bribe will not only earn the trading fees generated from swaps but also a share of the bribe.

As a result, token pairs with a bribe will have a higher APR than without one. We know that lockers will vote for the token pair with the highest APR to maximize their rewards. So, bribing will increase the number of votes that a token pair gets, which as mentioned before increases liquidity, … etc. The currency that lockers receive from bribes is decided by the bribe issuer. They can be paid out in either the ve(3,3) DEX’s native token or the bribe issuer’s native token. ($VELO or $SONNE respectively in an example of Velodrome being the ve(3,3) DEX and Sonne Finance being the bribe issuer)

Locked positions are now transferable

Before with Curve, a locked position was not transferrable. Ve(3,3) introduced a new idea that these positions can be transferrable, which in theory makes sense. If you know how bonds work, it is a similar structure. A basic example of how a bond works is the following: You purchase a semiannual bond for $1000 that has a maturity date of 4 years. Assuming an annual coupon rate of 1% and holding till maturity, you earn $5 every six months and then receive the $1000 at the end of 4 years, netting $1040. But bonds trade on the secondary market, so lets say you needed that $1000 in cash, you can sell it to someone else, generally for less than what you initially paid, to liquify your position.

Since these locked positions are now transferrable, people can sell their locked tokens on a secondary market just like bonds. As I said in theory this makes sense, but there is not a lot of demand currently for secondary market sales of these positions. At the end of the day, most crypto users are degens who don’t want to hold a position for months let alone years, so this doesn’t come as a huge surprise to me.

Lockers do not have their position diluted

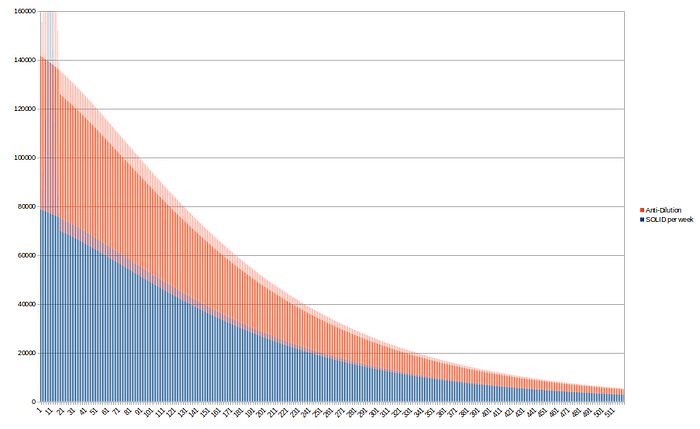

As we know from before, ve(3,3) emissions get distributed to liquidity providers. Emissions are newly issued tokens hence the total supply increases with emissions. To support long-term believers of the ve(3,3) DEX who lock their tokens, their position doesn’t get hurt by the token’s inflation. So they, in turn, earn a respective amount to hold their current position (if a locker had 1% of the total supply when first locking their tokens, they would still own 1% of the total supply in the future). Also, with a higher percentage of supply locked, rebase increases and dilution decreases. So, if you just hold the native token and do not lock it, you will be diluted by LP emissions. This incentivizes you to lock your tokens. To visualize, if 100% of the tokens are locked, all new emissions go to token lockers and the below graph will be all orange with no blue. This graph shows how emissions are distributed. (blue = emissions to LPers | orange = emissions to lockers):

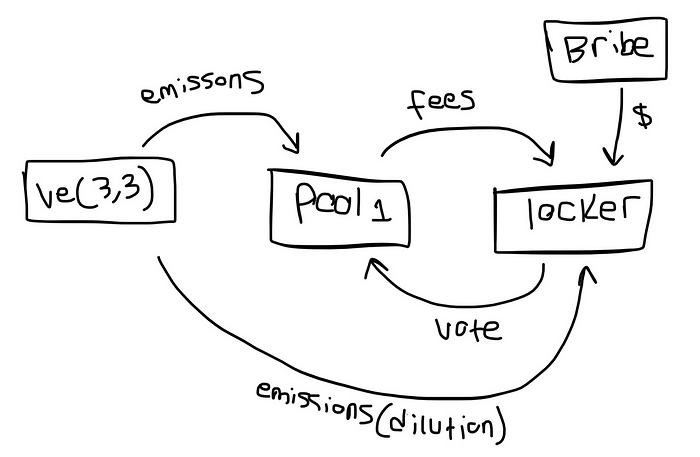

To wrap this section up here is a simplified diagram that shows how the tokens flow throughout a ve(3,3) DEX.

- Lockers place their vote on a pool

- Lockers receive trading fees from that pool

- Lockers receive any bribes placed on that pool

- Emissions are given to LPers based on the percentage of votes that pool receives

- Lockers are protected from dilution and receive proportion emissions to maintain their current position

Rise and Fall of Solidly

Andre Cronje had an ambitious vision with the first ve(3,3) DEX, Solidly, aiming to become the most autonomous and decentralized exchange. One of the main objectives of Solidly was to align protocol emissions with fees generated. The protocol achieved this by implementing the components described above.

The airdrop in January 2022 was the peak of Solidly’s hype. 20 veNFTs were to be released to Fantom’s top 20 DeFi protocols by TVL, and those chosen ones would own 25% of Solidly. As a result, the TVL of Fantom rose tremendously, from $3.7 billion in December 2020 to $12.2 billion at the launch of Solidly.

Why solidly failed?

As Cronje stated early on, he was building a protocol for protocols, which means that anyone is able to build upon Solidly and seek deeper liquidity if they wished to do so. Much hype and excitement was focused on this new decentralized exchange, particularly on its creator. So when Andrew Cronje announced through his collaborator Anton Nell that they were both leaving the defi/crypto space in March, everything was destroyed. SOLID lost 50% of its TVL in just a few hours. Further, the flaws in Solidly’s code and an unsustainable token emission schedule led to its decline.

What is next and why velodrome?

Now, Velodrome Finance comes into the picture, launched in March 2023 by a team that had created veDAO. It claims to address the main issues with Solidly whilst adding new improvements. To go over the main ones, Velodrome aims to maintain a better balance between LPers, voters, and external bribers by ensuring that rewards are claimable only after each epoch starts. They also added an on-chain governor to manage major protocol decisions such as determining tokens that are eligible for bribes and added an emergency “Commissaire” to kill unproductive bribes. Velodrome today stands as the largest ve(3,3) DEX and continues to drive the Optimism ecosystem.

All Comments